The written history of the Greeks doesn’t go back as far as that of say, Egypt. In fact, Herodotos, in the fifth century BC, thought that the Egyptians were the bees’ knees when it came to any number of things, the antiquity of their records among them. But the writings and art of the ancient Greeks—and their cultural emulators, inheritors, and adaptors, the Romans—have exercised an influence over European culture and imagination which is to all practical purposes unparalleled. Before the twentieth century, literature, art and architecture were saturated with classical allusions, and the so-called “classical education” was de rigueur. Even today, whether or not we realise it, we’re surrounded by classical references.

So perhaps it’s no surprise to find that from Robert E. Howard to the Stargate, SGA, and BSG television series, elements from Greek and Roman history and mythology have often appeared in science fiction and fantasy. Sometimes it’s been used purposefully, sometimes absentmindedly—and sometimes without anyone even realising that this particular interesting thing had classical roots to begin with.

I’m here to spend a little time talking about those classical elements. Since I’ve already mentioned Stargate, let’s start with the one of most obvious ones: the myth of Atlantis.

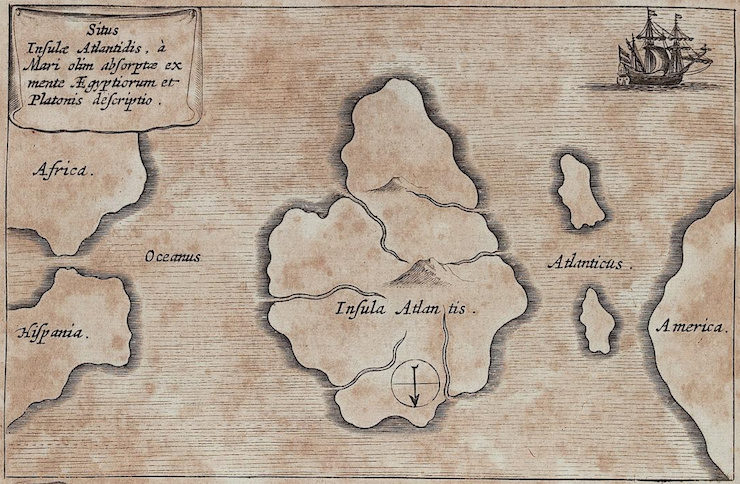

In the Atlantic Ocean, the story goes, long ago there was an island outside the Pillars of Hercules, which we today call the Straits of Gibraltar. It was a large island, large as Asia Minor and Libyan Africa combined, and it was ruled by a great dynasty which had conquered much of mainland Europe and Africa. When the Atlanteans reached Greece, Athens stood against them, first as a leader among allies, and later alone. But after coming to the edge of utter disaster, the Athenians recovered and triumphed over the Atlanteans, liberating all the peoples east of the Straits.

Later on, in the course of a single day terrible earthquakes and floods happened, killing the whole body of the fighting men of Athens, and causing Atlantis to sink beneath the seas.

This story is told in the Timaeus of Plato—as a prelude to a discussion of the creation and purpose of the cosmos—and taken up again in his unfinished Critias. The interlocutor, Critias, claims to have heard the tale from his grandfather, who had it from the famous sixth-century lawgiver Solon, who had it from Egyptian priests at Saïs, who’d told him their records went back nine thousand years to this time. Many notable modern scholars of Plato have suggested that he invented the idea of Atlantis, and the Atlanteans’ struggle with prehistoric Athens, to serve as an allegory for the events of his day, for the Athens of prehistory strongly resembles the imaginary “perfect city” of Plato’s Republic, and the Atlantis of prehistory can be conceived to resemble the Sparta of the fifth century. There’s certainly no evidence that this little tale predates Plato, at any rate, and his successors in antiquity didn’t seem to think he was recounting an elderly myth—but we’re not here to talk about its antecedents.

Its descendents are more than enough for going on with.

Let’s pass lightly over the centuries separating Plato (d. 348/7 BCE) and the modern period until Atlantis first pops up in the genre. (Very lightly, since my knowledge of late antique, medieval and Renaissance adaptations of the myth is scanty. Readers who know more are invited to contribute in comments!)

In Jules Verne’s 1869 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, the narrator Professor Arronax spends Chapter Nine sightseeing (in a diving apparatus) on part of the submerged continent:

“Further on, some remains of a gigantic aqueduct; here the high base of an Acropolis, with the floating outline of a Parthenon; there traces of a quay…” [1992:168]

Really, Atlantis has no business in the narrative except to heighten the sense of wonder of the vast, lost, unknowable depths of the ocean—and leaving aside the offended sensibilities of the modern archaeologist, it does that very well.

From the grandfather of science fiction, we pass (skipping over Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Maracot Deep) to Robert E. Howard’s Kull of Atlantis stories. These use an even further distant imaginary past (one in which Atlantean civilisation has not yet arisen) as their backdrop, and their context—like that of his later creation Conan, descendent of Atlanteans—is a mixture of classical, medieval, and orientalising elements.

In Tolkien’s Númenor, Atlantean echoes abound, and David Gemmell’s Jon Shannow series of novels make use of the Atlantis story. These, and many others, have adapted Atlantis to their own purposes. Atlantis has been a byword for lost grandeur for centuries. And Stargate in its first television incarnation is, of course, a byword for mythological reimagining. (Ancient gods were pyramid-building evil aliens! Except for the ancient gods who were good aliens! Archaeology and physics are exciting sciences! …Well, that’s something they did get right.) Stargate’s Atlanteans—the “Ancients”—weren’t merely superior civilised soldiers who had great wealth and maintained a strong military grasp on their territory: these Atlanteans were technologically—to say nothing of metaphysically—advanced superhumans. (A friend of mine pointed out that while the original Stargate series mostly portrayed the Atlanteans as annoyingly superior ascended beings, SGA, when it dwelt on them, gave a far higher emphasis to their ass-kicking abilities.)

The idea of Atlantis is a fundamentally versatile one, capable of being used as an allegory for warring city-states, as an image of forgotten splendour, or a cautionary tale of decline. But it’s not unique in its versatility, as I hope to show in my next post: classical myth, both in antiquity and in SFF, is very flexible.

Sometimes in more senses than one.

Article originally published in January 2011 as part of a longer series on SFF and the Classical Past.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, was published in 2017 by Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, where she’s been known to talk about even more books thanks to her Patreon supporters. Or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.

There is absolutely no doubt that Plato invented Atlantis for purposes of allegory. Good going Plato, establishing a persistent and flexible trope.

Jack Vance’s lyonesse trilogy is based on Atlantis myth and one if the best ever literary fantasies

I’ve long wondered how the Atlantis idea came to be so ubiquitous, to the point that many gullible people actually seem to believe it. I mean, I’m sure that Plato’s contemporaries never mistook his allegories for historical fact any more than people today genuinely believe in Mordor or Hogwarts. So I’ve wondered, when did it actually become a “myth?”

I did a Google Ngram search for “Atlantis,” and it turned up a few references to Plato’s Atlantis in some 17th-century essays, including one by Francis Bacon. There are also references in some translations of Ovid, Horace, and the like, so I guess there were other references in antiquity to Plato’s dialogues. There’s an 1816 book about “Pagan Idolatry” that mentions Atlantis as a legend.

Oh, this is interesting: A Popular Cyclopedia of History by Francis Durivage, 1835. It says there is “a controversy among modern authors” regarding the reality of Atlantis, and the author opines that it was probably real, since the Greeks had no reason to imagine such “a fable, which bore no relation to their history, and which was not calculated to affect their religious belief.” I guess he didn’t understand the idea of political allegory. There are one or two other early 19th-century books that seem to be discussing Atlantis as a genuine legend and possible historical fact. So it may not have shown up much in fiction before Verne, but it seems like there was a renewal of interest in Plato’s writings in the 17th century, and by the 19th century, the Atlantis myth had taken on a life of its own beyond Plato. Verne may have been one of the first to incorporate it in fiction, but the idea was being taken seriously by nonfiction writers well before him. Which makes sense, since Verne always strove to keep his fiction grounded in what was believed to be plausible science. So he wouldn’t have written about Atlantis if it weren’t taken seriously as a possibility by at least some scholars.

How widely was the whole “Atlantis” thing popularized by Blavatsky and the Theosophists, and/or Ignatius Donnelly?

One of the earlier books that I’m aware of (at least, one of the earlier books that had an Atlantis with “super-science”) was C.J. Cutliffe-Hyne’s Atlantis: The Lost Continent.

Atlantis also figured in some of Burroughs’ Tarzan novels, although not directly — the lost city of Opar was founded as an Atlantean colony.

My favorite non-fiction book on the topic is L. Sprague de Camp’s Lost Continents which, as you’d expect from the title, looks not just at the Atlantis myth, but also at Mu/Lemuria and others.

I had a vague memory of reading something, perhaps by Burroughs, perhaps even of Tarzan-series, where an underwater city was encased in a big glass dome which started to crack. By the time I could remember what I was (probably) thinking, hoopmanjh had beat me to Burroughs and Tarzan. But I think this is also what I remembered – although not Opar (the Atlantis-inspiration of which I do not argue but simply did not remember at the moment), but the book “Tarzan and the Forbidden City”, since I finally remembered enough to remember Tarzan really being there and Lavac dying. It has been almost twenty years since I read it, so I have only the most vague memories of what went on in there, but a quick leafing indicates that alas! It was probably only a small sacrifice-dome and not the whole city I remembered. Or was I mixing something of it with something other by him, on Barsoom or somewhere else? If anyone recognizes anything that it might have actually been (assuming my memory really is mixing things up), I’d appreciate the info :)

I know I’ve run into domed undersea cities many times, but I’m having trouble thinking of specific amounts — the only ones that spring to mind are in M.A.R. Barker’s Flamesong and Fritz Leiber’s “While the Sea-King’s Away” (a Fafhrd & the Gray Mouser story), and neither of them are really the sort of thing you’re asking about.

The question of how much Plato invented is a fascinating one. Obviously sunken-land myths, with varying degrees of historical foundation, exist all over the world, and it would hardly be surprising if he’d come across them.

It’s very different from his other uses of parables. Usually he straight-up announces it’s a parable, or takes an existing story and reworks it according to his rhetorical needs (e.g. the Ring of Gyges story in The Republic, a radical rewrite of existing legends about the historical King Gyges). But with Atlantis, he goes out of his way to provide an authentic-looking pedigree for a story he clearly expects to be new to his audience. It seems like a mischievous hoax, except that that’s hardly in character. A Gyges-level rewrite of a lost folk tale, perhaps? The echoes of the Thera eruption have been overstated, but do exist.

Diodorus Siculus has a certain amount to say about a race called Atlanteans, who IIRC fought a war against the Gorgons, but he may simply mean people from the Atlas Mountains.

@@.-@: I don’t know about the Theosophists and Atlantis, but the story was well enough known by the early 20th century that E. Nesbit included an Atlantis chapter in a novel for children, The Story of the Amulet, 1906. Said amulet allows the children, and the occasional “learned gentleman” tag-along, to travel through time:

It’s a lovely city, too, all marble and gold and copper, palaces and parks and temples, and people riding on tame mammoths (yes, mammoths)– but there’s an odd and ominous rumbling out to sea….

Nesbit had friends among the theosophists and occultists, as well as the socialists and Fabians and such, and was herself a big influence on later generations of writers. So there’s another potential link.

@7, I can tell you for a fact that the story did NOT come from Egypt via Solon, that was all literary invention. Why Plato decided to do it that way I can’t say. He may well have been influenced by tales of distant cities and lands lost to the sea, the latter being a persistent theme in many genuine mythologies.

Atlantis may be (loosely) based on a genuine historical catastrophe. Santorini went catastrophically kaboom around 1500 BCE, taking out the Minoans into the bargain. Two pivotal civilisations in the Mediterranean at the same time. Yes, it’s not in the Atlantic, but I’ve seen a number of TV programmes which argue that this is the likely source of Atlantis.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minoan_eruption

Just gonna say: Aquaman. Do you know how disappointed I was as a kid when I found out the legend of Atlantis had nothing to do with people adapted to live underwater?

According to Dear Dolphin, humans mistook the back of a ginormous sleeping whale named Joe for an island and built Atlantis on it. Then Joe awoke and wanted to submerge, but his friend the sea serpent couldn’t convince the people that they were n a whale. Then it vanished. Turns out they relocated inside the whale, though he claims he doesn’t know how that happened. And now the city is ruled by a dugong princess. That’s the version of the legend I chose to believe. (No, Tor spell-check, I mean dugong. Not dungeon).

@8: Atlantis also featured in a short story by E. Nesbit, “Accidental Magic,” in her delightful collection The Magic World.

What about Homer’s “Scheria”, another name for Atlantis, in The Odyssey

@13/T Del Vecchio: I had to look up Scheria. It’s hardly legitimate to call it “another name for Atlantis.” In The Odyssey, it was another name for Phaeacia, the last place Odysseus visited before returning home to Ithaca. It was described as a fantastically advanced civilization with ships that could be steered by thought alone, but it has nothing in common with Atlantis beyond the generalized trope of being fantastically advanced. The first attempt to equate it with Atlantis dates from 1888. I suppose it’s possible that Plato was influenced by Phaeacia/Scheria when he made up Atlantis, but there are no doubt plenty of other such miraculously advanced fictional kingdoms in ancient literature and myth.

The article author wrote, parenthetically:

Well, the three shows didn’t belabor the point, but keep in mind that “the Ancients” (under various names — Lanteans, “the Ancestors,” etc.) cover at least a million years — by the usual lights that’s a species, not a single civilization, and it’s not surprising that their societal emphasis and architectural tropes changed over that interval. Dr. Jackson et al were fantastically lucky that the written language was mostly unchanged, no matter what era of techno-artifact they encountered.

(They’re one example of the trope of “round numbers to express fantastic antiquity” which sometimes bothers me. See also: The Transformers. “They’re been in stasis for four million years! And before that, they were at war for five million years!” Our language causes u to go from millennia, to ten thousand, to million. Nobody is ever “13,500 years old” or “85,000” or “230,000, plus or minus 20,000.”)

The Ancients/Atlanteans were the definition of irresponsible progenitors.

The early historians had a habit of exaggerating, conflating facts, and making up things out of whole cloth in their works. Thucydides was perhaps the first to make any effort at getting his facts straight.

At the risk of reprising the TVTropes page on Atlantis:

In the anime TV series Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water (1990, 39 episodes) the Atlanteans were an alien colony on Earth who had created humanity, fallen and abandoned their city, moved to a secluded corner of Africa, and inspired a bunch of hooded thugs to grandiose world-conquering plans. The early episodes utilize some elements of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, such as a submersible called Nautilus (actually a refurbished spacecraft) and a captain named Nemo.

Disney’s Atlantis: The Lost Empire (2001) – Sometimes compared to Nadia but IMHO closer to Stargate (1994). The island of Atlantis is not only submerged beneath the sea, but into a cavern; as of 20cen it’s still populated, but its 8,000-year-old monarch has, in a fit of shame, obliterated its history.

The TV series Transformers: Cybertron (2005, 26 episodes) (Japanese version: Transformers Galaxy Force) in which the idea of “Atlantis” as a forgotten cultural wellspring is adapted as a Cybertronian colony ship of that name on Earth, and multiplied to three other planets, with ships named Hyperborea, Lemuria, and Ogygia (the English-language scriptwriters decided that Mu would sound silly to anglophone viewers).

@17, Herodotus, aka ‘the Father of History’ was an honest reporter, you can believe him on anything he saw with his own eyes. Unfortunately he didn’t think it was his job to vet his sources and repeated the most outrageous tall tales with a straight face.

Heh, you guys are gonna get me into trouble, because I love the article and am open, slightly, to the slim possibility that Atlantis did not exist. *fine with sounding like a flake*

@18/Phillip Thorne: One of the weirder mentions of Atlantis in Japanese film is in the original Gamera, where Gamera is said to have been one of a species of giant turtles that lived in Atlantis, even though he’s found in the Arctic. Decades later, in the vastly superior Gamera reboot trilogy in the ’90s, his new origin was that he was genetically engineered by the ancient Atlanteans to fight against the Gyaos, pterosaur-like monsters that had arisen from an abuse of Atlantean genetic engineering, and that he was created for the purpose of preserving the balance of nature and fighting things that threatened it. Gamera in those movies had sort of a human “herald,” an adolescent girl who was psychically linked to him by an orichalcum pendant.

@9 Well, obviously. Pretty sure I never suggested it did, only that some kind of tradition might have preceded Plato, which we appear to agree on.

Heinlein’s Lost Legacy uses Atlantis explicitly – “After a great war their main bases in Mu and Atlantis sank” Wikipedia but like Numenor many of the numbers have been rubbed off or altered.

Then again rather than enduring Atlantis may be swamped by sinking lands that are Not Atlantis. This from David Drake on his own Tor series:

One of my personal favorite versions is Clark Ashton Smith’s Poseidonis, a series of 1930s weird fantasy stories set on Poseidonis, the last outpost of foundering Atlantis. (Smith took the idea, possibly from the Theosophists?, that Atlantis didn’t sink all at once, but in fits and starts over a series of centuries or millennia.)

Many, many years ago I read a comic with an Atlantis story. I went and researched it so I could tell you which it was: The Marvel Family #10, in which the Marvels battle the Sivana Family. The whole thing is now online, but I got a nasty pop-up that forced me to close the tab to escape it, so I hesitate to share the link with you all here.

Going by faint memory, then; the Sivanas had a new weapon that could even destroy the Marvel Family, but it needed a really rare element to power it which existed in Atlantis. The two families split up travelling through time to past and future as well as dealing with the present. The element changed over time and grew more powerful so that one day Atlantis could be raised again, and there was a line of scientists that actually continued to be scientists for thousands of years who were dedicated to this task, which at last did occur despite the Sivanas stealing samples of the element over the millenia.

Now I want to read this again!

And then of course, there is the Marvel Comics version of Atlantis, which sunk like the others, but whose people adapted and became an aquatic species.

And the societies that don’t have sunken-city myths have something analogous. Like the pre-Islam Arabs for example; they don’t have a sunken city myth, presumably because they lived in a desert, but they have A’ad (aka Irem of the Pillars). Big rich city, got wicked, God nuked it. The Jews had Sodom and Gomorrah. All just form of what Pterry called the “if you don’t stop it you’ll go blind” myth.

Smith took the idea, possibly from the Theosophists?, that Atlantis didn’t sink all at once, but in fits and starts over a series of centuries or millennia.

Well, that definitely happened as the Ice Ages ended, no doubt in various other parts of the world but certainly in Doggerland (now the southern North Sea).

@27/ajay: Thinking it over, I suppose it was fairly common in antiquity and prehistory for large settlements or towns to die out or be abandoned due to disease or drought or climate shifts. So most every culture would know of some important cities or settlements or communities that were around for a while and then ceased to exist, and their stories about the cool stuff that was once there but got lost would get exaggerated with each generation’s retelling, until you ended up with legends about magnificent, super-advanced ancient civilizations that ceased to exist in great, dramatic cataclysms.

Only Plato’s Atlantis isn’t super advanced. Rich and splendid yes, advanced even by Ancient Greek standards not so much. That twist was added by theosophists and the like.

Plato did not intend Atlantis to be ideal or admirable. His invented Athens was the ideal.

Basically what we have here is a couple of millenia worth of misaimed fandom.